Wisconsin Fim Festival: An unexpected gem, a Zucchini, and a farewell

Sunday | April 9, 2017 open printable version

open printable version

Clash (2016)

Kristin here:

Three more films from this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival.

Clash (Eshtebak, 2016)

David and I were intrigued by the festival’s program notes describing Egyptian director Mohamed Diab’s second feature, Clash, as taking place with the camera entirely confined to the interior of a police paddy-wagon. This kind of limitation can be a fruitful device, as it was in the Israeli film Lebanon; there the action took place inside a military tank. Clash turned out to be a real discovery, the best film I saw at the Festival (putting aside A Quiet Passion, which we had already seen at the Vancouver International Film Festival.).

Diab’s paddy-wagon has the advantage of rows of barred windows and a door, so that we can frequently see what’s happening outside. The film is set in the summer of 2013, when there were protests, often turning violent, in the wake of the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi and his replacement by the current president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. The truck moves through Cairo, encountering waves of such protests, and it gradually fills with a collection of people with various religions, beliefs, and cultures–supporters of Morsi’s party, the Muslim Brotherhood; others who oppose him; Christians; a homeless man; a nurse; and two journalists–with arguments and violence erupting inside the vehicle as well as outside.

Diab had to tread a fine line in his depiction of these people, since his basic theme is that they all must learn to cooperate to some extent if they hope to survive the baking heat, tear gas, gunfire, police bullying, and the anger of the mobs outside the truck. Officially the Muslim Brotherhood is considered a terrorist organization in Egypt, though Diab manages a fairly even-handed treatment of its members and supporters. Remarkably the censors did not require any changes to the film.

Just as remarkably, Diab was able to stage huge, convincingly terrifying riots in Cairo’s streets and highways (above). In a brief interview at Cannes last year, where Clash was shown in the Un Certain Regard section, he was asked if the shoot was difficult.

Very. You are risking your life because people might mistake the shoot for a protest, or might mistake you for the police. And there are haters of both, who can shoot you. It took us months of preparation. Egyptians to whom I’ve shown the film are blown away because they know that what we did is almost impossible.

He makes similar remarks in a question-and-answer session at the London Film Festival; his discussion of the film’s techniques comes from about 9:30 to 13:50.

The characters in the truck are constantly in danger, both from each other and from the rioters, and the action is absolutely riveting. There are a few lulls to vary the pace and to allow the prisoners to deal with their wounds and try to work out a strategy to protect themselves, but otherwise the suspense is maintained at a high level. A climactic scene in which rioters attack the truck, flashing laser pointers into it and trying to tip it over is handled, as Variety‘s review put it, with “brilliantly choreographed pandemonium.”

Clash was a huge success in Egypt. It was released in France in September and is already out on region 2 DVD (French subtitles only) there. Its festival life seems to be drawing to a close. It’s due for theatrical release in the UK and Ireland on April 21 and presumably will come out on Blu-ray and/or DVD. You can get a good sense of the film from the online trailers, the European one and especially the Egyptian one, though the film is not nearly so fast-cut.

My Life as a Zucchini (Ma vie de courgette, 2016)

2016 was a good year for animation. Kubo and the Two Strings, The Red Turtle, Moana, and Finding Dory were excellent as well. (I thought Zootopia was overrated.) Add My Life as a Zucchini to that list. This being Madison and the Wisconsin Film Festival being a university-sponsored event, we saw it with French subtitles rather than dubbed.

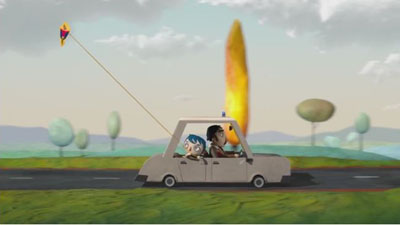

The style of the film, with its bright colors and cute, big-headed characters (above and at the bottom), makes it seem aimed at children, and the story is presented almost entirely through the viewpoints of Zucchini and the other children he meets. Yet children younger than teenagers would probably find parts of it incomprehensible or disturbing. The boys indulge in naïve but somewhat explicit speculation about sex. Zucchini’s beer-swilling mother apparently dies in an accident that he inadvertently causes, though this happens offscreen. He is taken by a sympathetic policeman to a small home for young children in the countryside. Not all are orphans, as it is made clear that one girl was taken away from her sexually abusive father and some of the others come from homes ruined by addiction or violence. Zucchini gets bullied and teased before finally being accepted.

All this makes for a strain of melancholy running through the film, but there is considerable humor to counter it, and the ending is happy.

Like Kubo, My Life as a Zucchini is puppet animation. Clearly it was done on a much lower budget, without the laser-printed changeable faces that make Laika’s characters so expressive. Charmingly, if distractingly, the clothes of the puppets occasionally shift positions, betraying the handling by the animators between frames–as when the red star on Zucchini’s T-shirt inadvertently takes on a life of its own. But on the whole, the filmmakers have used simple means to give their figures considerable expressivity.

The nomination of My Life as a Zucchini for the Best Animated Feature Oscar came as something of a surprise. Foreign films do show up in that category, but this one had its widest American release in a mere 53 theaters. It came out on February 24 and is still in 22 theaters, having grossed $286,154 as of April 6. (Presumably that does not count the two WFF screenings; the one we went to was sold out.) The DVD and Blu-ray versions are available for pre-orders on Amazon. The description says that both the original French-language soundtrack and the English-dubbed one are included.

Afterimage (Powidoki, 2016)

Afterimage premiered at the Toronto Film Festical almost exactly a month before the death of director Andrzej Wajda. It deals with the co-founder of Polish Constructivism, Wladyslaw Strzeminski, who helped create the Blok group in Warsaw in 1923. The plot covers only Strzeminski’s last years, but we get a strong sense of his entire career through gallery scenes displaying his work.

Socialist Realism was imposed upon Polish artists after the country came under the sway of the USSR in the wake of World War II. The film’s action starts with Strzeminski’s being fired in 1950 by the Ministry of Culture and Art because he refused to adhere to the doctrine. We see his stubborn resistance and the attempts by his adoring students to help him find respect and other work. Up to his death in 1952, he is oppressed by intransigent officials bent on denying him even the most demeaning jobs.

Reviewers have treated Afterimage with the respect due a veteran auteur late in a six-decade-plus career, but they deem it to lack the energy and appeal of his earlier work. Certainly compared with Wajda’s films of the 1950s and 1960s (we’ve commented briefly on two from the 1960s), Afterimage is a fairly conventional film. It’s beautifully made, as Wajda clearly had a considerable budget to recreate the historical look of Soviet-era buildings and streets of the early 1950s. To anyone unfamiliar with the impact that Socialist Realism could have on the avant-garde artists in the USSR and elsewhere starting in the 1930s, the film provides a vivid example. The film also contains an excellent performance by Boguslaw Linda, perhaps best known as the lead in Kieslowski’s Blind Chance.

Strzeminski, being the victim of persecution from almost the beginning, automatically becomes a sympathetic character. He also lost an arm and a leg in 1916 during World War I. (The budget is on display again in the fact that undetectable special effects removed Linda’s own arm and leg.) It is hinted that if he had been grievously injured in World War II, some allowances might be made, but having it happen during the Tsarist war of the pre-revolutionary era earns him no credit with the officials.

Yet Strzeminski loses some of our sympathy through his treatment of his teenage daughter Nika. She is interested in his art, closely examining the “Neoplastic Room” he helped create in the Lodz Museum–just before it is dismantled and put into storage as part of Strzeminski’s punishement. Nika also tries to help her father, cooking for him and trying to get him to cut back on smoking, but his ingracious rejection of her efforts helps drive her to live in a girls’ dormitory near her school. He remarks matter-of-factly after Nika leaves, “She will have a hard life.”

Our thanks to Graham Swindoll of Kino Lorber for help with this entry. As well, of course we owe a debt of gratitude to the WFF programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser.

My Life as a Zucchini (2016)